One reason I write art historical fiction is to bring “untouchable legends” to life — to show Michelangelo and Leonardo, and Raphael (#AmazonAssociate) not as divine geniuses, but as men. Struggling, passionate, broken, complex men.

But even though this is my mission, I never thought Andy Warhol needed to be humanized. Michelangelo and Leonardo were flattened out by others. By history. But WARHOL? No one did this to WARHOL… He did it to himself. He is pure conceit. He wanted to become a THING, and he did. He made himself into a shallow celebrity as flattened out and reproduced as his soup cans and Jackie O’s.

WARHOL isn’t a person. WARHOL is a pop image.

Right?

Wrong.

In The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Warhol is not a monochromatic reproduction, but human: complex, brilliant, broken, self-conscious, conceited, sweet, awkward, strange, graceful, vulnerable. And after my visit, I am obsessed with the man behind the facade.

I will do my best to give you a glimpse of the Andy I met inside this museum, but you must go see it for yourself. WARHOL was a creation of the artist’s brain, of New York City, of pop culture. But Andy? He’s still in Pittsburgh.

I found a young man named Andy Warhola, his family/given name, sitting on the stoop of his parents’ house in Pittsburgh, awkward but longing to be noticed. This was a boy, like so many boys I’ve known, dreaming of something beyond. I saw his childhood: son of immigrants, sometimes sick, a regular life in so many ways.

I saw how his imagination was his escape from all that regularity. He is an artist from the time he is young. His art doesn’t explode like some nuclear flash; it grows in him like a tapeworm, until it consumes him, too.

His art changes the world. His talent is so white hot, it’s impossible to touch. But for the first time, I don’t see pure conceit; I see pain and doubt fueling his rush toward the spotlight.

Under those flashy images, I feel his desperation — desperation for fame, to put up a facade, to create something spectacular; something not regular. This Andy reminds me of people I know in Hollywood: brilliant, but so desperate for fame that the need to be noticed consumes them. All that pop — that color and flatness and intentional shallowness — hides a deep well of desperation running like molten lava.

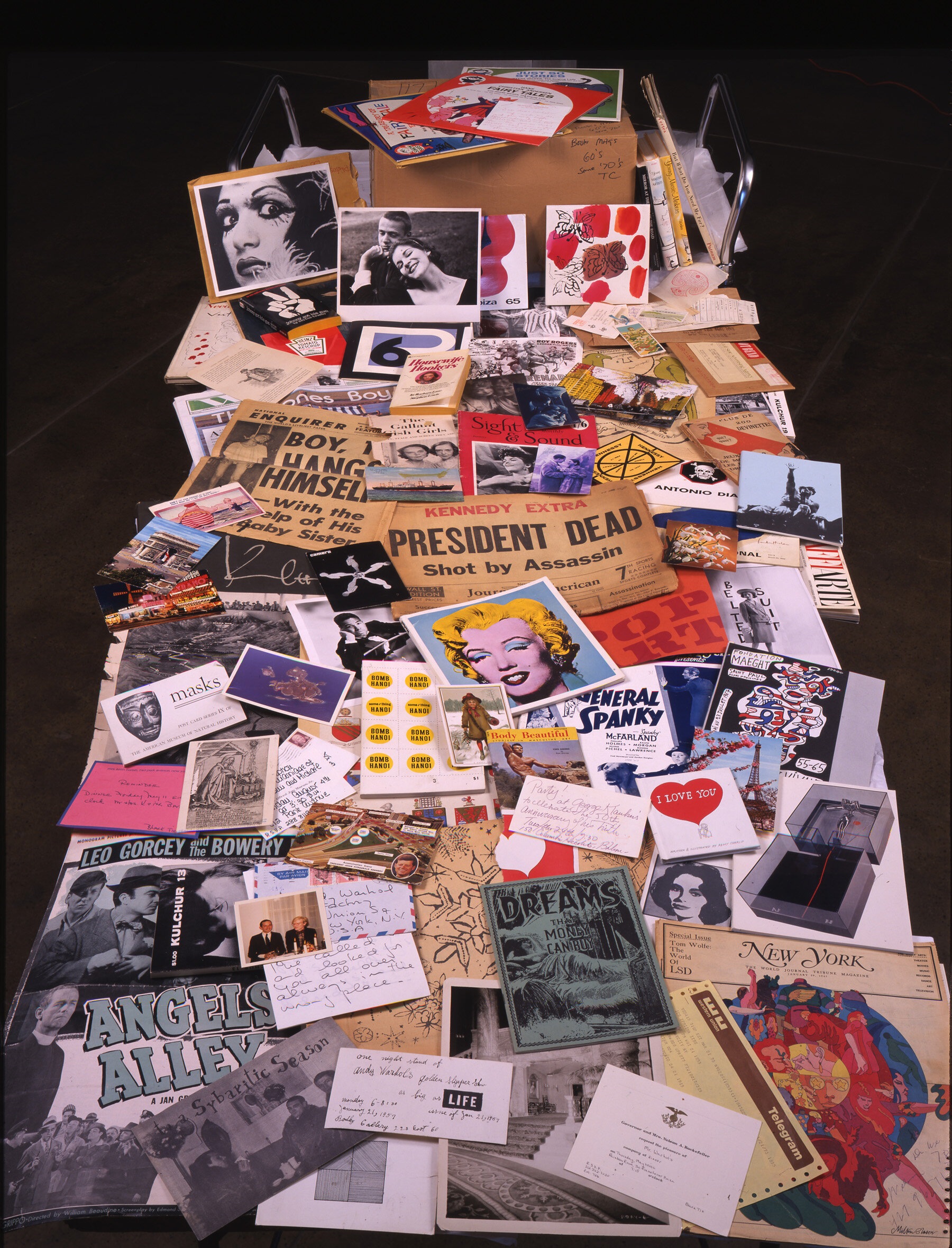

Did you know Andy created a series of Time Capsules? I knew about them, intellectually, but I’d never seen them before. In 1974, he started collecting mementos from his daily life — letters, newspaper clippings, toys, photos, food — placing it all in cardboard boxes. The contents of those boxes provide a unique glimpse into Andy’s mind and times. He kept making them until his death in 1987; he created 612 in all.

These time capsules look like the inside of my junk drawer. Andy’s Time Capsules contain the same strange, meaningless — yet meaningful — crap we all collect. But when an artist meticulously collects 612 boxes of the mundane, does that crap begin to look brilliant? In a creepy I-get-where-this-guy-is-coming-from sort of way, yes.

And then there was that picture. By photographer David Montgomery. I knew Andy had been shot by one of his female film stars in 1968, but it always seemed like part of the WARHOL show: a big, dramatic moment; fodder for press; a cleverly constructed plot-twist. It never seemed serious to me. I’ve seen other, more posed black-and-white photos of Warhol’s wounds; but those pictures always seemed like pages out of a fashion magazine, celebrating the scars as part of the myth.

But this picture — this picture captured the struggle. Andy looks haunted; the joy of the public persona is gone. He has a very human reaction to mortality: fear. He can’t hide it, and in that picture, he doesn’t try.

The other place where I saw him — the real him — was in the video room where he was recording a tribute to Man Ray. It’s just him, on camera, struggling to think of something to say. He isn’t profound. He isn’t larger than life. He says, “Man Ray” over and over again. He fidgets. His eyes dart. He asks for people to rescue him from the filming, then, “Man Ray, Man Ray, Man Ray, Man Ray…” He is uncomfortable. Exposed. And I loved him for letting himself be so exposed. I see people I know: people who want to be looked at, but who are uncomfortable when the focus rests solely on them.

In that moment, Andy isn’t so flat anymore.

We flatten out all of our celebrities, don’t we? We turn them into a laughable slide show. When they fail, get divorced or shot, we treat it like gossip. And we blame them. You chose this life when you chose to become an actor, musician, writer, performer. You chose to turn yourself into a piece of mass marketed pop culture to be consumed and replicated over and over again until it is destroyed…

But do any of our celebrities really choose this? Or are they driven by something larger than themselves, to go after their craft in spite of the fame, not because of it? And even if they do chase fame, do they cease being people when they become celebrity?

Perhaps Andy did choose it. Perhaps he really did want to flatten himself out. But this museum is proof that he failed. He couldn’t take the humanity out of himself any more than he could take the humanity out of Jackie O, Marilyn, Elvis and Mao… He tried, but failed on all accounts. Thankfully, because the human truth behind the facade is much more interesting.

###

All photos courtesy of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh