Alyssa Palombo is one of my favorite historical fiction writers of my era — the Italian Renaissance. Two of her novels The Most Beautiful Woman in Florence (about Botticelli’s model) and her most recent The Borgia Confessions (about Cesare Borgia and family) bring the Italian Renaissance entertainingly to life…

(If you buy books through these links, this site gets a small commission at no extra cost to you!)

So I wanted to ask this history buff and classically trained musician some questions relating to her view of the Italian Renaissance. If you’re a reader (or a book club moderator!) looking for more info on papal courts, Renaissance models, AND music, look no further than this interview with the fabulous Alyssa Palombo.

Stephanie Storey: You’ve written about Vivaldi, Botticelli, the Borgias… When you pick a topic for one of your novels, do you pick subject-matter that you already know intimately or do you choose topics about which you want to learn more?

Alyssa Palombo: It’s been a little of both so far, honestly. With my first novel (The Violinist of Venice, about Vivaldi) I knew only the basics about Vivaldi and very little about Venice or Venetian history when I started writing. I just had this idea that wouldn’t leave me alone, and as a musician the music was my way into the story. I did the research as I went, and of course because of that some things about the story changed, but I think it all worked out! Conversely, with The Borgia Confessions I knew much more and that was WHY I wanted to write the book. I’ve been a bit obsessed with the Borgias since I was a teenager, so I had a really solid base of information when I first approached the project. Of course, I sometimes think that the more you know, the more you realize you need to know, and so that book was still quite research intense for me.

SS: Your most recent book, Borgia Confessions, centers around Pope Alexander VI’s son, Cesare Borgia, and a servant for the pope’s family. Many of my readers are surprised to know that popes once had children… Can you help my readers understand how/why this happened during the Renaissance?

A Glass of Wine with Cesare Borgia by John Collier (1893), Ipswich Museum and Art Gallery

AP: I think the simplest explanation is that priests and popes are men, are human, just like anyone else. While of course clerics in the Catholic Church were sworn to celibacy then as now, it was hardly unusual for churchmen to have mistresses and children, and for this to be something of an open secret, especially if the man in question was someone very powerful and influential. Sadly, things haven’t changed much in that the wealthy and powerful tend to get away with doing whatever they want. Often cardinals and popes would refer to their children as nieces and nephews, but Pope Alexander VI was a bit different in that he acknowledged his children as such.

SS: Pope Alexander was pope during the years covered in my novel Oil and Marble, when Michelangelo & Leonardo were battling it out in Florence. How did Florentines feel about Pope Alexander? How much influence did he have over life in Florence at the time?

AP: The biggest example of Pope Alexander VI’s influence in Florence was in regards to the matter of Girolamo Savonarola. It’s quite a long story – too long to do it justice here – but the basics for readers who may not be familiar are as follows: Girolamo Savonarola was a Dominican friar who rose to prominence in the Florentine monastery of San Marco in the late 1400s. He began preaching against the decadence of the Medici family – Florence’s ruling family at the time – and against what he saw as the pagan art, literature, and philosophy that made the Renaissance what it was. His sermons were pretty old school: basically anything pleasurable or enjoyable or even fun was considered sinful (this is a bit of an oversimplification, but you get the idea). He famously hosted “Bonfires of the Vanities” in which people were encouraged – and sometimes extorted – to publicly burn “sinful” items such as books, paintings, fine clothing, dice and cards, etc. He grew enormously in popularity and had ardent followers at all levels of society. He also took to preaching against the pope – specifically Pope Alexander VI – and against the corruption of the church at the time. He even called out the fact that the pope and cardinals has mistresses and children, which was a pretty daring move, but one he made in seeking to purify the church, as he put it. He also succeeded in driving the Medici from Florence completely for a time, and essentially ruled Florence through its republican council. Pope Alexander, of course, couldn’t let such a challenge to his authority stand – even though of course the things Savonarola was saying about him and the church were true – and had him excommunicated, meaning he could no longer preach.

Francesco Rosselli (Italian) The Execution of Savonarola, 16th century, Galleria Corsini

That didn’t stop Savonarola for long, and eventually the situation in Florence grew so volatile, with those in support of the friar and those passionately opposed, that violence erupted and Savonarola was eventually arrested. Pope Alexander let it be known that he expected the friar to be executed for heresy, and Florence obliged him, so Savonarola was eventually burned at the stake.

So, with all that being said, Florentines’ opinion on Pope Alexander likely depended on their opinion of Savonarola. If they were followers of the friar’s, they probably despised the pope and the corruption rampant in the Vatican (which, for what it’s worth, neither began nor ended with Pope Alexander). Those who were not taken with the friar and his teachings – including some artists and intellectuals engaging with the Greek literature and philosophy that helped spark the Renaissance – might have looked to Pope Alexander as a possible ally in ridding their city of Savonarola. I would also imagine that there were many who may have agreed with Savonarola’s overall message, at least in part, but were uncomfortable at his preaching against the pope and the church.

SS: Cesare Borgia’s military campaigns play a major role in the plot of Oil and Marble. Can you help us imagine the kind of fear his campaigns created all across the Italian peninsula?

The fear was probably quite considerable – after all, a few years before, a French army led by King Charles had run through Italy mostly unopposed with the goal of conquering Naples, so no doubt the people of the Italian peninsula felt like they were living the same nightmare over again. The different city-states of Italy were often at war with one another, so while warfare was nothing new to the people of Italy at this time, the French army led by Cesare Borgia was a rather different beast than the companies of mercenaries that Italy was used to seeing: bigger, more organized, and with better weaponry. With that said, and not to defend Cesare Borgia particularly, but there is some evidence that life in some of the small city-states he conquered actually got better for the people living there after he deposed the sometimes cruel and murderous duke or lord who was in charge. Whether that compensated for the psychological toll warfare would have taken on the people living in these areas I can’t say. But war and its effect on everyday people not involved in the power games of popes and kings is something I explore in The Borgia Confessions as well.

Much of my new novel, Raphael, Painter in Rome, is set inside the Vatican. Can you give us your favorite story about what life would’ve been like in the papal courts at the time?

Hmm, this isn’t a story particularly, but when I think of the Vatican during this time period what most comes to mind is opulence. The church was extremely wealthy at this time – namely from the practice of selling indulgences and Masses for the souls of departed loved ones – and so the pope and cardinals (and sometimes their children) lived in relative splendor. The jeweled vestments and crosses and tableware and the feasts that were served…it was quite excessive, or it could be; it depended on who the pope was. Aesthetically it was all fabulous, but it’s a bit hard to swallow from an institution that preached against things like greed and vanity. Some of this opulence is to our benefit today, though, in that they commissioned beautiful works of art and architecture that we can still see and admire. So there’s that! All this opulence, of course, is what eventually sparked the Reformation, and it isn’t hard to see why.

SS: Your novel, The Most Beautiful Woman in Florence, centers around a woman who becomes one of Botticelli’s models. I get this question often from book clubs: Was it common for women to model during the Renaissance and what would that process have been like?

Highborn or noble women wouldn’t have been artists’ models as a general rule, though they would sit for portraits that may have been commissioned of them. And often in paintings of religious scenes for wealthy patrons, the artist would include members of the family as saints or other figures in the work.

Venus of Urbino, Titian, 1534, Uffizi Gallery in Florence

Outside of this, though, an artist might hire a sex worker for a model – for instance, the woman in Titian’s famous Venus of Urbino was a Venetian courtesan. I’m not sure how widespread this practice actually was, but it likely happened at least sometimes. I also read somewhere recently that many Renaissance artists studied Greek and Roman statues and sometimes used those as models, which is interesting.

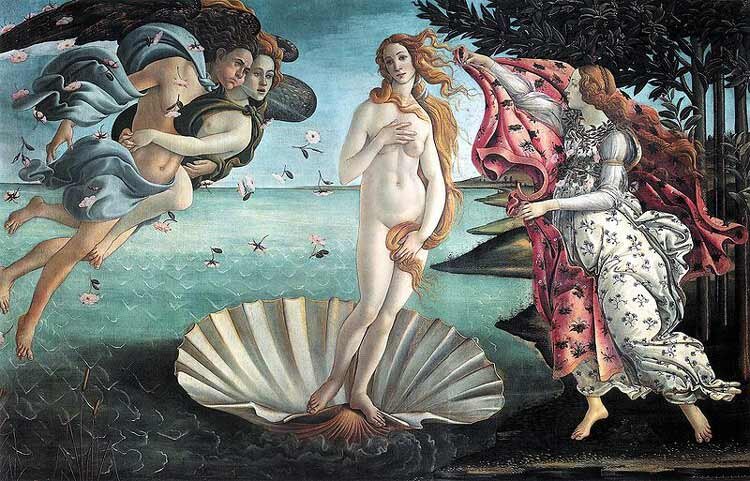

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, 1480s, Uffizi Gallery in Florence

So it’s unlikely that Simonetta Vespucci would have posed nude for Sandro Botticelli, as she did in my novel, but it’s true that he painted her into his works for much of his life, and hey, that’s the fun of fiction, isn’t it?

SS: The Most Beautiful Woman in Florence also dives quite deeply into the Medici family. What’s the most surprising thing you learned about this family of wealthy bankers and art patrons?

Portrait of Lucrezia Tornabuoni by Domenico Ghirlandaio, c.1475, at National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

AP: In researching that book I loved learning about Lucrezia Tornabuoni de’ Medici, mother of Lorenzo the Magnificent. She is a fascinating historical lady that I wish was more well known! She advised her husband, Piero, and later her son on political matters, and even personally negotiated Lorenzo’s marriage to Clarice Orsini, a member of a prominent Roman family. She did a lot of charitable work, particularly with widows and orphans, and would provide dowries to girls from poor families so that they could marry when they otherwise might not have been able to. She was also a poet and a playwright in addition to being a patron of the arts. She was highly intelligent and accomplished, a real Renaissance woman.

SS: In addition to being a writer, you’re also a trained musician and music plays a large part in many of your stories. Does studying music change the way you write or give you unique perspective into the creative process that non-musicians might be lacking?

I think that simply being a huge music lover – both as a performer and as a listener – allows me to channel that love of music onto the page. And certainly I drew from my own experiences as a music student in writing some of the music lesson scenes in both The Violinist of Venice and The Spellbook of Katrina Van Tassel. And while I don’t write music, as Adriana does in Violinist, I was able to apply my own knowledge of creativity and the creative process to the scenes where she is composing. I do think that having experience in another form of art helps bring a depth to my writing that it may not otherwise have, yes. And I think that participating in another kind of art is just good for my soul!

ALYSSA PALOMBO is the author of The Violinist of Venice, The Most Beautiful Woman in Florence, The Spellbook of Katrina Van Tassel, and The Borgia Confessions. She is a recent graduate of Canisius College with degrees in English and creative writing, respectively. A passionate music lover, she is a classically trained musician as well as a big fan of heavy metal. When not writing, she can be found reading, hanging out with her friends, traveling, or planning for next Halloween. She lives in Buffalo, New York.

Want to learn more about Alyssa and her books? Visit her website at AlyssaPalombo.com, follow her on Twitter @AlyssInWnderlnd, or on Instagram @Alyssinwnderlnd