Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature (on now at the Denver Art Museum until Feb 2, 2020) is one of the best retrospectives of Monet’s work and life that I have ever seen.

The exhibition is giant, showcasing 100 of Monet’s paintings brought in from 80 collections in 15 countries. It spans two floors, multiple galleries, and Monet’s entire career—not just the famous pieces from late in his life, but early works that chronicle Monet’s evolution as an artist. (The Denver Art Museum is also this exhibition’s only stop in the US, so if you want to see it, you’ll have to get yourself to Denver before February.)

But it wasn’t only the size of this exhibition that struck me; I was in awe of the number of works brought in from private collections from all over the world, trotted out especially for this. And it’s the first time in history that one of my favorite Monet paintings — Night Effect — has been exhibited in the US. (One of my favorites because we usually think of Monet as light and bright and airy, but here he’s delving into how darkness reflects off the water of Le Havre Harbor)

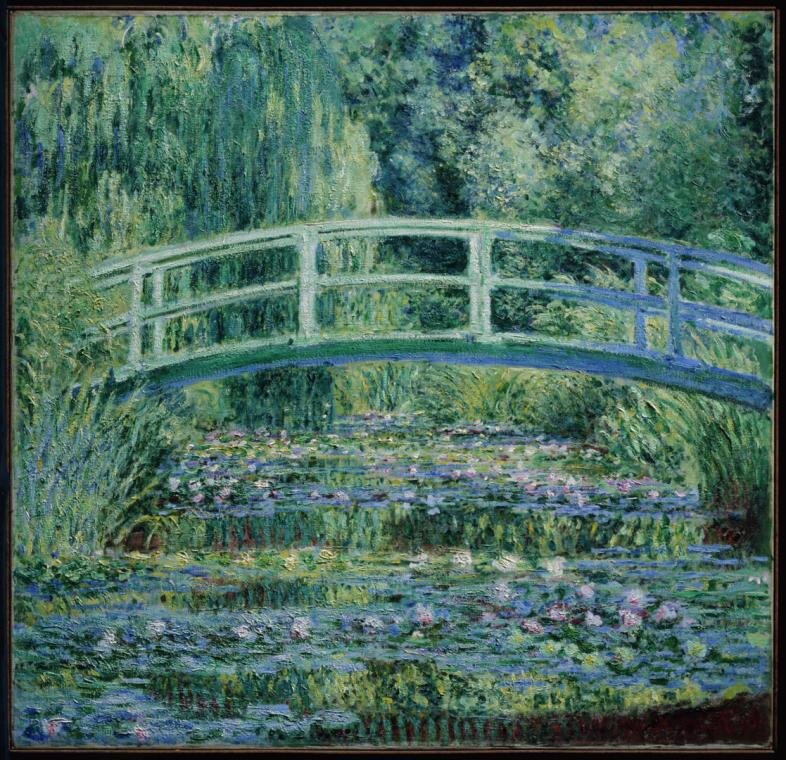

The fleeting passage of time, moving water, changing light—even if that light is darkness—these were Monet’s obsessions.

This exhibition is entitled The Truth of Nature because it focuses on the artist’s obsession with landscape painting—even though he developed his art at a time of intense modernization in Paris, he always clung to landscape.

Why? Why water and light and trees and green?

The Truth of Nature is an accurate representation of the exhibit, but I might have also titled it “The Truth of Monet” because it showed me a TRUTH about the artist himself: it showed me his unwavering desire to create the impossible.

I attended this exhibition with a dear friend, and we were BOTH struck by how this particular layout of paintings tracked Monet’s insatiable desire to capture the uncapturable; he spent his life trying to depict the constantly changing, moving, breathing nature of light and water and air… but he tried to capture those fleeting elements on a static, two-dimensional canvas in a single frame using a medium—paint—that dries into an unmovable surface. HOW could he capture movement and change in a medium designed NOT TO CHANGE once it’s completed? And why was he chasing such an impossible dream?

Why was he so obsessed?

At times, as I walked through this exhibit, I feared that Monet had spent his life desperately chasing the impossible—traveling to far-flung places, trying every conceivable brushstroke and color, and building entire gardens to help him on his quest, but never achieving his dream… But at other times, standing in front of his paintings, I was struck by how he HAD, no doubt, managed to capture a fleeing moment of light and color and movement dancing across a single, static image, proving that, if you try hard enough, the impossible is always possible.

Earlier this year, I took a trip to Normandy where I got to visit Monet’s hometown of Le Havre and the stomping grounds of his youth along the northern coast. When you’re wandering around Normandy, watching how the constantly changing light and weather reflect off the rough waters of the English Channel, you get this powerful understanding of how and why Monet chased such an obsession his entire life: it was his entire world.

Until now, I thought you had to travel to Normandy in order to feel this…

But now, walking around this exhibit—the way the images are grouped together, the way they hop and leap and spread across the galleries—you’re struck with that exact same feeling as walking along the coasts in Normandy… Monet didn’t have a choice but to be obsessed with light, water, with CHANGE — because it was all around him.

At least, for the next few months, you don’t have to fly to France to feel this insight. You only have to get yourself to Denver.

YOU MUST ORDER TICKETS BEFORE YOU GO!

The exhibition is selling out and there are days that are already completely sold out.